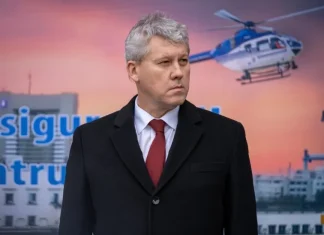

Author: Cozmin Gușă

I have read or at least browsed almost all the books written about Putin in the last 20 years, some are tributes, others anti-Putin propaganda, only about 2-3 of them can be useful to those who want to understand the power of The Kremlin under the leadership of the new Tsar. The other days I finished reading a so-called novel, “The Wizzard of the Kremlin”, by Giuliano Da Empoli, the most popular French writer of the moment, of Italian-Swiss origins, a 50-year-old man, professor at the prestigious Science Po in Paris, former political advisor to Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi. The hero of his book is not Putin, but Vladislav Surkov, who was Putin’s right-hand man for 20 years, nicknamed the “New Machiavelli” or “Putin’s Rasputin”. In the book he goes by the name of Vadim Baranov, but it is easy to guess that, possibly through a trusted intermediary, Surkov shared with Da Empoli many of the real situations of his work with the New Tsar of Russia, as Putin is nicknamed in Romanian, but also in the current expression in the press. Throughout my life, through my work as a politician, consultant or president of the Romanian Judo Federation, I have known several close people or even friends of Putin, thus being able to confront my information about the real way of being of the president Russia with what is presented in the volume, and this is the reason why I say that this book is the most useful for those who want to understand what Putin is like in reality or how Russia is run. I selected a few fragments that I present below, somewhat at random, it was also difficult to do otherwise because the book is worth reading in its entirety, it is also very well written by this Frenchman, whom I confess I discovered only now.

Vadim Baranov, the character by which Vladislav Surkov is described, describes his job as a TV producer in Russia at the end of the 90s, on one of the mogul Boris Berezovsky’s televisions:

“We were making a barbaric and vulgar television, as the nature of this environment demands. The Americans had nothing left to teach us, in fact we were the ones pushing the limits of trash. From time to time, however, the immemorial Russian soul emerged from the depths. At one point, we came up with the idea of a big patriotic show. Asking our audience to tell us who their heroes are, the characters on which the pride of mother Russia is based, we expected the big names: Tolstoy, Pushkin, Andrei Rublev, or whatever, a singer, an actor, as it were happen in the West. But what did the spectators give us, the informed mass of the common people used to bending their backs and looking away? Only names of dictators. Their heroes, the founders of the homeland, coincided with a list of bloody autocrats: Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, Lenin, Stalin. We were forced to falsify the results to make Aleksandr Nevsky win, a warrior at least, not an exterminator. But the one who collected the most votes was Stalin. Stalin, do you realize? Then I understood that Russia will never become a country like the others. Not that there was any doubt.”

Putin was still the head of the FSB, and Boris Berezovsky introduces Surkov, who tries to convince Putin to take over as prime minister with a future presidential bid on the line, in a run-down Russia under the leadership of a drunk and used Boris Yeltsin:

“This is why we believe that we need a different thread, which contains both the elements of continuity and those of the break with the past. By becoming Prime Minister, Vladimir Vladimirovich, you will automatically assume the role of legitimate authority, something fundamental to Russians, who do not seek adventure and who, especially at this time, want stability and security. On the other hand, your figure will immediately produce an obvious contrasting effect with that of the current president. You are young, sporty, energetic, you give the feeling that you can take full responsibility for the command. Your background in security services is a guarantee of reliability. Being a man of few words will work in your favor. Russians are tired of charlatans. They want to be ruled with a strong hand to restore order to the streets and restore the moral authority of the state.

That is why the electoral campaign we have in mind will not consist of gatherings and promises. In fact, what we are thinking about is the exact opposite of such a campaign. The bet will be not to appear as a politician like everyone else.

You see, Vladimir Vladimirovich, I don’t know politics very well, but I know what a show is. can I ask you a question? Do you know who the greatest actress of all time is?”

Little, expressionless, he shook his head.

“Greta Garbo. And you know why? Because the idol that refuses its status strengthens its power. Mystery generates energy. Distance fuels awe.”

A few days later, Putin invited Surkov to the table, telling him the following:

“Your analysis of the past few days surprised me, continued Putin. I know your path. I think you could make a valuable contribution to my work, whatever it may be, now or later. But first we need to make one point clear. As much as I respect Berezovsky, I’m not willing to put myself in his hands. If you accept my offer, Vadim Alexeevich (Surkov’s first name in the book, n.r.), you will work exclusively for me. The administration will guarantee you a lower salary, I’m afraid, than what you are getting now, and you will do it in such a way as to make sure that it is enough for you. I will not tolerate any bonus or benefit coming from Boris or anyone else. If you care about money, keep working privately. He who is in the service of the state must put the public interest above all others, including his own. If you undertake this undertaking, I think it is needless to tell you that I have the means to ensure that you will keep it.”

Accepting Putin’s proposal to become his adviser, winning the presidential election, Surkov attends the Putin-Clinton meeting in New York, on the occasion of the UN General Assembly. On this occasion, Clinton brings back to their memory an embarrassing episode with Yeltsin, and after the end of the meeting, Surkov describes it as follows:

“This scene came back to the Tsar’s memory the moment Clinton asked him for news about old Boris. So he immediately made him understand that things would be different with him. No more back slapping and laughter. Clinton was obviously disappointed. He believed that from now on all Russian presidents will be nothing but good hotel porters, guardians of the largest gas resources of the planet for the benefit of American multinationals. For once, he and his advisers left a little less smiling than they had come. But what did they expect?

“If some cannibals took power in Moscow, the Tsar poured out his fire during the return flight, the United States would immediately recognize them as a legitimate government, provided it did not affect their interests and treated them like masters. The problem is they’re convinced they’ve won the Cold War, see? When in fact the Soviet Union did not lose him. The Cold War ended because the Russian people ended a regime that oppressed them. We were not defeated, we freed ourselves from a dictatorship. It’s not the same thing. The Westerners also contributed to the democratization of Eastern Europe, but they should not forget that the greatest contribution was made by the Russians. We brought down the Berlin Wall, they didn’t tear it down. We dissolved the Warsaw Pact and extended our hands to them in peace, not surrender. It wouldn’t hurt to be reminded of that from time to time.”

Relevant scene from the moment when Surkov was preparing the strategy for a new presidential election campaign:

“The Tsar was reading a document and remained silent for a few minutes. Then, without looking up from the paper in front of him, he asked me:

“How’s my popularity rating, Vadia?

“About sixty percent, Mr. President.”

- Good. And you know who is higher than me?

- No one, Mr. President. The nearest competitor is about twelve percent away.

“That’s not true, Vadia.” Look up, there is a Russian leader who is more popular than me.”

I didn’t understand where he was going.

“Stalin. Grandpa is more popular than me today. If we were face to face in some election, he would tear me to pieces!”

The Tsar’s face had acquired the mineral consistency I had learned to recognize. I refrained from making any comment.

“You intellectuals are convinced that things are the way they are because people have forgotten. According to you, they don’t remember the purges and massacres. And that is precisely why you continue to publish article after article and book after book about 1937, gulags, victims of Stalinism, etc. You think Stalin is popular despite the massacres. Well, you’re wrong, he’s popular because of the massacres, because at least he knew how to deal with mobsters and traitors.”

The book recounts the meeting between Surkov and Kasparov, the world chess champion and a staunch opponent of Putin, with whom Putin’s advisor develops a polemic:

“I burst out laughing: “This shows at least that the Russians haven’t completely lost their sense of humor! Kasparov, seriously, do you know what sovereign democracy means?

I’m not a political scientist (answers Kasparov, n.r.), but as a chess player I’d say it’s more or less the opposite of a game. In chess, the rules stay the same, but the winner changes all the time. In your sovereign democracy, the rules change, but the winner is always the same.

I must admit that the great champion had a prompt reply. The worldly people around us were fidgeting like groupies at a concert.

“May be. I know politics isn’t your thing, but tell me, Kasparov, didn’t the CDU stay in power for twenty years in Germany after World War II? And the Liberal Democratic Party, for forty years in Japan? You liberals think that in Russia political culture is the archaic product of ignorance. Consider our customs, our traditions an obstacle to progress. You want to imitate the Westerners, but you miss the point.”

Kasparov was now looking at me with a frankly hostile air.

“If you want to taste something sweet, you have to eat the candy, not the wrapper. To conquer freedom, you must assimilate its substance, not its form. Repeat the Slogans you learned in Washington and Berlin, and in the meantime fill our streets with candy wrappers. You are just like the Bourbons, don’t forget or learn anything: you had your chance and turned Russia into dust. Ever since you lost your power, you dream of regaining it to complete your work. As for us, we completely bypassed the issue, learned the lesson of the West and adapted it to the Russian reality. Sovereign democracy corresponds to the foundations of Russian political culture. This is why people are on our side. Only you teachers haven’t understood yet.

- But I’m not a teacher!

- Of course not. You are a chess champion.”

Kasparov sensed the irony and did not appreciate it. As a son of the Caucasus, he pursed his lips in a dissuasive expression.

“There’s no game more violent than chess, you know.”

I smiled gently at him.

“You don’t know what you’re talking about, professor: politics is infinitely more violent.

“But it’s not a game.”

— For amateurs, it’s not a game. Instead, believe me, for professionals, it’s the only game that’s really worth playing. “

Kasparov looked at me like I was crazy. I also thought he was stifling a shiver.”

The famous scene in which Angela Merkel is received by Putin with his labrador, a job criticized for a long time by the world press:

“The shot with the labrador does not belong to me. But we have to admit it’s a brilliant idea, if a bit brutal like most of the Tsar’s initiatives. The chancellor had prepared for a normal meeting. Immaculate, in a black suit and boots bought, as usual, from the supermarket, without any paper on it. Because he was studying everything beforehand: the meticulous handouts made by his team, the letterhead of the ministries, and the plain paper memos distilled by the Federal Republic’s security services. Nights and days spent devouring data, drawing geopolitical scenarios with the same precision as when he did his lab experiments during his university career. The result is that the Chancellor always arrived fresh and sure of herself, bad as anyone knows she can afford, with the geometric power of those Linders and those Konzernes behind her. But that day, nothing could have prepared her for what awaited her the moment she made her entrance into the hall where Koni, the Tsar’s giant black labrador, was to be held.

To understand the situation correctly, you must know that the implacable chancellor had a phobia of dogs. Over the years, she had tamed more ferocious beasts in the arena of world politics than all the circus trainers at a Games, but a dog, any dog, even the most insignificant one, managed to awaken in her the primal fear she had experienced as a child for eight years, when only a miracle had prevented the neighbor’s rottweiler from tearing her to pieces under her father’s horrified eyes.

Imagine then the scene in the Kremlin that day. Besides, you don’t even have to imagine it, because the pictures are online. The chancellor grinning wryly, while shiny-furred Koni twirls her around. The chancellor stiffens in her chair as Koni comes to her playfully looking for comfort. The chancellor is on the verge of a nervous breakdown when Koni slips her muzzle into her lap to sniff her new friend’s scent. The Tsar, next to him, smiles relaxed, legs apart: “Are you sure you don’t mind the dog, Mrs. Merkel? I could kick him out, but he’s so cute, you know. I can hardly part with him.”

The labrador. This is when the Tsar decided to take off his gloves and start playing the game as he had learned on the courts of Leningrad, where you didn’t have time to touch the ball because someone had already put a knee in your shins. There you always had to prove that you were a little bit crazier than the others if you wanted the bullies to keep from riding you. Very high level politics is much the same. Gilded halls, pickets of honor, official processions passing through the streets closed to traffic, but then, basically, the same logic as in the schoolyard, where the bullies impose their law and where the only way to make yourself respected is to hit the knee.

In the early years when he appeared on the international stage, the Tsar had remained a bit withdrawn, with the classic attitude of the Russian who never has his papers in order and must submit to the scrutiny of much more civilized judges. The eternal complex of the fringe barbarian, who must atone for five centuries of massacres, culminating in the apocalypse of real socialism.”

Surkov meets Yevgeny Prigozhin, Putin’s so-called chef:

“On one of these occasions I met Evgheni Prigojin. Four or five of us had met in the private salon of a restaurant full of mirrors and chandeliers. Putin had introduced me as the owner of the place to a rather insignificant, bald guy, who smiled modestly, and indeed, throughout the meal, he had played his part, describing the various dishes, serving famous French wines, and being at all times at the disposal of the Tsar , ready to satisfy any gastronomic demand. Dressed in a silver tie as if for a wedding, he addressed us kindly, then, more dryly, the staff who served us. Only at the end of the meal did Putin suggest that he stay with us. The table was immersed in an increasingly alcoholic conversation about the comparative merits of several European escort agencies. The Czar, who evidently had not resorted to their services, took no part in the discussion, but watched it with an amused expression to which all present were attentive, ready to change the subject at once if it changed. Prigozhin had blended in naturally, the butler’s aplomb giving way to the good-natured skepticism that befitted members of the magic circle of old friends. At first he had some success with some frothy anecdotes about his nocturnal adventures in the Balearic Islands. After which he diverted the conversation to his latest entrepreneurial adventure: the purchase of a gigantic farmland on the shores of the Black Sea, which he intended to turn into a rocket plantation. “You have no idea how hard it is to find decent arugula in Russia,” he repeated, half seriously, half amusedly, to his teasing companions. But at one point the Tsar interrupted him and turned to me.

“As you can see, Evgheni is not without initiative. He’s also into international business, and I think he could lend us a hand with some of the issues we’re discussing these days, right, Genia?”

At these words, the restaurateur’s eyes lit up, while Putin continued: “It would be useful if you could talk to each other, Vadia.”

You have to understand one thing: The Tsar never says anything specific, but he also doesn’t say anything at random. If he bothers to make a suggestion that, for example, his political adviser should meet with a restaurateur in St. Petersburg to discuss Russian foreign policy, however absurd it may seem, the idea must be taken seriously and taken to fulfillment.”

The end of the collaborative relationship with Putin is described, after 20 years in which Surkov was always at the Tsar’s right:

“I left first, that’s all. I wasn’t fooled by the familiarity. The trust of a prince is not a privilege, but a condemnation: the one who reveals his secret to someone becomes his slave, and princes cannot bear slavery. Wanting to break the mirror that sends back your own image is a common practice. Moreover, the prince may repay small favors, but when they become too great and he no longer knows how to repay them, he is tempted to solve the problem by removing the cause.

The Tsar was never capable of affection, at most of habit. And from a certain point on, he lost the habit of meeting with me. In Novo-Ogariovo (Putin’s residence near Moscow, n.r.), he cut three kilometers worth of forest around his dacha. He wakes up late in the morning, after which he has a breakfast consisting of fresh eggs sent by Patriarch Kiril from his farm. Then he works out in the gym watching the news. If there is something urgent, there he reads the confidential notes and conveys his dispositions. Then swims a kilometer in the pool. At the edge of the pool, the first visitors of the day, ministers, advisers, heads of large companies, summoned last night or the same morning, wait patiently for the Tsar to come out of the water to hand him a bathrobe and entertain him very briefly with a matter or other.

Only at the beginning of the afternoon does the presidential procession set off for the Kremlin. The streets were closed to traffic half an hour before. At every intersection, a police car ensures that the Tsar’s solitude is not disturbed. From Novo-Ogariovo to the Kremlin, Putin crosses almost the entire capital, frozen in his passage, arrives at the office, and only there begins the real working day, which sometimes ends at the first glimmers of dawn. The Tsar’s entire existence is out of step with that of normal people, imposing a distortion on those forced to work with him. One man does not sleep at night, and he has trained everyone who matters in Moscow to share his vigil until three or four in the morning. Knowing the chief’s nocturnal habits, a hundred ministers, high officials and generals lie awake awaiting a call. And each keeps a small phalanx of assistants and secretaries by his side. Thus, the lights of the ministries remain on, and the Moscow power lost its sleep again, as in the time of Stalin.

(…)

Sometimes things end badly, because the powerful tolerate autonomy the least. But when I resigned the Tsar’s mind was elsewhere. I think he took my withdrawal with relief: he no longer needed me. Inventing a new order requires a certain amount of imagination, but the blind devotion of the servants is enough to enforce its observance.

No one took my place. The Labrador is the only adviser in whom Putin has full confidence. He makes him run around the park, goes to the office with him. Otherwise, the Tsar is completely alone. From time to time, a bodyguard appears, a servant or courtier appears, summoned for some reason. That’s all. He has neither wife nor children with him. As for friends, he knows that on the stage he has reached, the very idea of having such a thing is unimaginable. The Tsar lives in a world where even the best of friends turn into courtiers or implacable enemies, more often than not both.

In the West, your leaders are like teenagers, they can’t be alone, they are always looking for someone to watch them, you get the impression that if they had to spend a day in a room without company, they would dissolve into air like a breath of warm wind. Our Tsar, on the contrary, lives in solitude and feeds on it. In meditation he accumulates the strength which surprises so many of your observers. Over time, it became almost an element of nature, like the sky or the wind. You have forgotten what it means to live like an adult, rooted in reality. You think that a leader is a kind of animator, you want some leaders who look like you, who are on your level. Distance maintains authority. Like God, the King can be the object of excitement, but without being excited himself, his nature is necessarily indifferent. His face has already taken on the marble pallor of immortality.

At this level, we are well past the aspiration for the beautiful funeral I was telling you about. The Tsar’s ideal would rather be a cemetery where he stands alone, upright, the sole survivor of all his enemies and even his friends, parents and children. Maybe even Koni’s. Of all living things. “Caligula wants the skulls of all men to be on one neck, so that he can annihilate the whole world at one blow.” Pure power. This is what the Tsar has become. Or maybe it was that way from the beginning. The only throne that will bring him peace is death.”

I wish you a pleasant reading of a book from which you will learn a lot about the texture of power in the Kremlin!